बाउको धुरी छैन

Father Has No Roof Over His Head

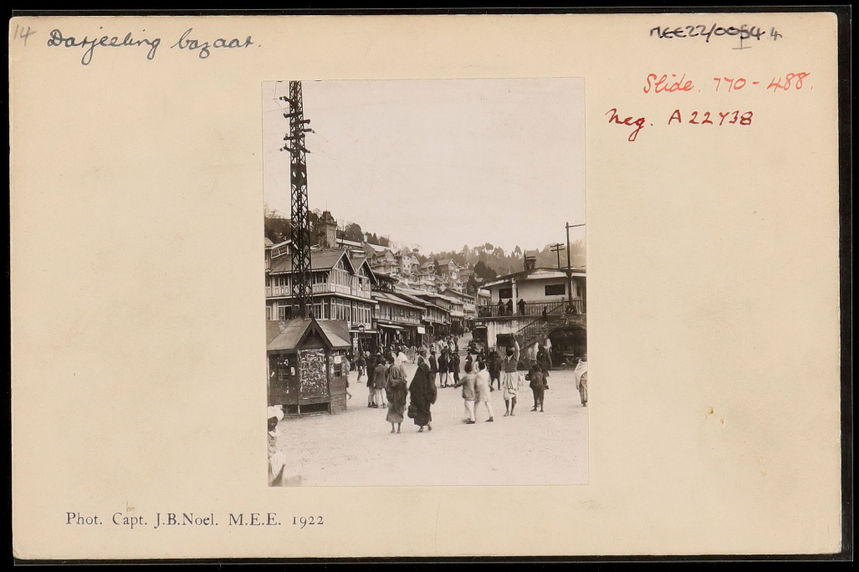

Even after a century, as our region’s history was never recorded the way imperial histories were, we are still in the process of uncovering a marginalised past. The story of Everest began in our hills- Darjeeling, Kalimpong, and Sikkim; long before Nepal opened to foreign exploration. Before borders were mapped and routes were formalised, our places were the gateways to Himalayan journeys. Serving as centres of recruitment, training, trade, and lived knowledge. While the world celebrated Everest as a site of conquest and heroism, another story unfolded quietly. Of our porters, guides, interpreters, and traders who carried expeditions forward- shaping paths, camps, and ways of survival. Himalayan people bore dual responsibilities - the burden of the British empire alongside the arduous weight of European imperial expeditions, while navigating mountains sacred to their communities. In Himalayan cultures, mountains are not merely landscapes, they are deities and protectors. Everest is one such sacred peak, known locally as ‘Chomolungma’ in Tibet and ‘Sagarmatha’ in Nepal, worshipped and revered long before the foreign climbers arrived. The local people’s labour was their livelihood but it included reverence, a bridge between survival and devotion. Their work took them far from home, where they endured hardship in service of others’ ambitions without a roof over their heads.

One among the forgotten names was Ang Tshering Sherpa (1904-2002), a 20 year old porter in the ‘1924 Everest Expedition’. Born in Nepal’s Thame, he migrated to Darjeeling in 1920 seeking a livelihood. He would return four times to Everest (1924, 1933, 1952, and 1960), yet never to summit due to his deeply religious beliefs. In 1934, he joined the German Nanga Parbat expedition which would end in tragedy. Having suffered severe frostbite on his feet and hospitalised for over a year, he would stop climbing for almost two decades. Resuming only in 1952 and continuing to climb until 69 years of age as a Sardar. In 1954, he was part of the Daily Mail British Joint Yeti Expedition, accompanied by his son Dawa Temba. He was the first person to discover a footprint of the Yeti. He was highly decorated having received multiple awards like the German Red Cross, Himalayan Club Tiger Medal, and so on. But his life as a mountaineer was shaped by altitude, risk, and responsibility. There are multiple narratives of him adopting the children of deceased porters while extending a helping hand to porters. For him and many other locals, climbing mountains was not a dream. It was just another source of livelihood, but a dangerous and relentless profession, undertaken to sustain their families at home. His family members shared that Ang Tshering used to say, “We went to earn money. No one had the ambition to climb Everest”.

Another story is that of Chheten Wangdi, an interpreter for the ‘1921 Everest Expedition’. Born in Darjeeling and later settled in Pedong, Kalimpong. Wangdi was an expert in all Tibetan dialects and English, an alumnus of Calcutta Boys’ High School. He had an illustrious career, having served as a Captain in the Tibetan army and then the Indian army, stationed in Egypt during World War I. Post the Everest expedition, he taught Tibetan in the Delhi School of Foreign Languages and established Pedong’s first flour and grain mill. Chheten Wangdi is also said to have been involved in aiding the recognition of Bhutia as a Scheduled Tribe. Remarkably, he was among the few non-European collaborators paid at par with his English counterparts, a rarity for the time. His story is a blend of intellect and cultural negotiation, highlighting the often overlooked local expertise that made the Everest expeditions possible.

This is also a story of the people and places they left behind, where survival was uncertain, anxiety was constant, and families endured absence and economic precarity. To satisfy the ambition and ego of imperial expeditions, these men walked away from their homes with no certainty of return. They left behind parents, wives, and children who lived in constant waiting, wondering whether their children, husbands and fathers were alive, injured, or lost to the mountain. As colonial officers toasted to success, these men endured severe injuries, terrain, weather, hunger, and death. They returned season after season, not for recognition or glory, but because the mountains were their source of livelihood.

This exhibition seeks to question the portrayal of the local people involved in imperial mountain expeditions. These men were skilled high-altitude porters, interpreters, sardars, and guides. Their labour built the routes, camps, and knowledge that made Everest ‘climbable’ for the foreigners who became household names. While the people who bore great risks remained unnamed, their courage and sacrifices forgotten, their stories unwritten. Through this project, we aim to preserve these personal histories, photographs, and documents that reimagine Everest’s legacy. By sharing these stories, we are building a collective archive - one that centers local lives and experiences behind the expeditions to the world’s most iconic peak.

The title “बाउको धुरी छैन” (Father Has No Roof Over His Head) comes from a family memory passed down through generations. Ang Tshering Sherpa’s wife, Passang Diki Sherpa would tell their children that their migrant father has no roof over his head as his work kept him away from home, far in the high mountains. In Himalayan culture, the ‘Dhuri’ is the roof ridge, the backbone of a house’s roof. To have none is to live without shelter, permanence, or rest. “बाउको धुरी छैन” as an exhibition, seeks to remember and preserve the collective memory of the Himalayan labourers. It hopes to remember lives long overlooked. Asserting that the true backbone of Everest expedition history was never the summit, but the porters who bore the burdens, the interpreters who bridged words and worlds,the sacred mountains and traditions they honoured and the families and land they left behind.

This project is part of THE OTHER EVERESTS -

Other Everests is a new interdisciplinary network that takes as its starting point the centenary of the post-war British Everest campaigns of 1921-1924. It will bring together international scholars, archivists, curators, learned and professional societies and the UK mountaineering community to critically assess the legacy of the Everest expeditions and to re-evaluate the symbolic, political and cultural status of Everest in the contemporary world.

In collaboration